Ron Berger

One of the aims of my contribution to the Active McFarland blog is to educate readers and offer political analyses and historical background that place our voting preferences and grassroots political work in broader context. In an earlier post, I cited Paul Starr's observation that America seems "stuck--unable to make significant progress on critical issues such as climate change, rising economic inequality, and immigration. . . . Democrats and Republicans, liberals and conservatives, are now so sharply opposed to each other that they are unable to find common ground" (September 15, 2015).

In his book Our Divided Political Heart: The Battle for the American Idea in an Age of Discontent, historian and political commentator E. J. Dionne puts this divide in historical perspective. Its roots, he argues, go back to the era in which the United States was founded. When the founders devised the U.S. Constitution, they were concerned with establishing a government that promoted both individual and communal values. What at the time was understood to be a "republican" sensibility, they believed that the individual liberty "they so prized depended upon virtues and forms of solidarity" that could not be sustained without a commitment to "the preservation of a public life." While they were concerned about government encroachment on individual liberty, they also allowed for substantial government involvement in the economy in order to ensure shared prosperity for all. According to Dionne, the constitutional mandate for this latter tradition can be found in the "general welfare" clause of the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution: "We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect Union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessing of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America" (my emphasis).

The debate between Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) and Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804) over the role of the states versus the federal government reflects these different strands of the American tradition. Jefferson was a believer in democratic self-rule, which also made him a supporter of states' rights vis-à-vis the federal government because, he thought, states were closer to the people. Hamilton, on the other hand, believed that a strong national government was necessary for the development of shared prosperity. While Jefferson's views were closely tied to an agrarian economy, Hamilton thought the country's future laid in manufacturing and that the federal government was necessary to coordinate the emerging marketplace both within the borders of the United States and between the United States and other countries.

The issue of slavery arguably lies at the heart of this debate as it evolved in the 1800s. In the slave-holding states of the South, as Dionne notes, the fear that any expansion of the federal government would eventually allow for the abolition of slavery "led southern defenders of bondage to oppose national initiatives," however much these initiatives might be beneficial to the nation. What this debate often misses, as we reflect upon it in the contemporary era, is that the federal government was deeply involved in the lives of the American people from the beginning of the country. Take the case of the Federal Marine Hospital System, which was signed into law by President John Adams in 1798. This law amounted to a system of socialized medicine for seaman who were injured or fell ill on the job. Additionally, the early U.S. postal service dwarfed its European counterparts in its scope and capacity to deliver mail at affordable prices--this another instance of the federal government penetrating the hinterland in ways that were central to what the nation's founders hoped to provide to the citizenry.

Historian Brian Balogh also notes that the stark division we now assume between the public and private sectors of our society was not assumed during the early years of the country, when corporations were understood as "publicly crafted organizations granted special privileges in order to meet public service requirements." It was only in the late 1800s, as a result of an unprecedented U.S. Supreme Court decision, that corporations were treated as private entities that retained legal rights to operate in ways not connected to the broader public good. Prior to that time, according to historian Michael Sandel, "Jefferson's conviction that the economic life of the nation should be judged for its capacity to cultivate in citizens the qualities of character that self-government requires" enjoyed widespread support. Dionne adds that contemporary conservatives are certainly not wrong to view individual enterprise and achievement as cornerstones of the founders' vision, but what they tend to overlook is that "these were not the only values, or even the primary values, that [were] celebrated, and that government--at the federal, state, and local levels--was an active agent in promoting national development and shared prosperity."

Dionne also argues that contemporary conservatives who believe that the government has no role to play in regulating a market economy are the heirs to ideas that did not emerge in the United States until the so-called Gilded Age of the last three decades of the 1800s. The Gilded Age, a term coined by Mark Twain, was an era of rapid economic growth in the industrial sector of the economy, including the mining and steel sectors, as well as the national railroad system, which allowed for the growth of commercial agriculture that needed a way to transport crops to new markets. These developments were accompanied by the emergence of corporate monopolies and rising inequality--because without government intervention the "big fish ate the little fish"--and gave rise to corporate ideologies and legal theories that postulated that corporations were persons within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment (which prohibited the government from depriving "persons born or naturalized in the United States . . . of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law"). In turn, these developments spawned an anti-corporate social movement, which had two distinct yet overlapping strands: populism and progressivism. It is to these movements that I now turn.

What is Populism?

Contemporary use of the term "populism" has varied meanings, but populism as a historical movement has its roots among disaffected farmers of the 1870s and 1880s who were concerned about falling crop prices and rising production costs. Their grievances were most pointedly directed at the excessive transportation and interest rates charged by railroad operators and bank lenders, respectively, and they called for greater government regulation of these industries.

In the 1890s an alliance of farmers joined with worker and other reform-minded groups to form the People's Party, also known as the Populist Party, to advocate on behalf of the "common people" vis-à-vis the elite. These populists not only called for more government regulation, but also for a graduated income tax, a shorter workday, and electoral reforms such as the secret ballot and direct election of senators (rather than election by state legislatures).

This coalition was also instrumental to the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. Trusts were essentially cooperative business arrangements that circumvented competition in the economic marketplace, and the Sherman Act prohibited such arrangements if they resulted in a restraint of trade (including cooperative agreements to fix prices) or the monopolization of an industry. More generally, the Sherman Act was an expression of the view that government intervention was necessary for the preservation of economic competition. As economist Robert Reich recently observed, the notion of a "free market" independent of government is a myth. Without government defining the rules of the economy, the marketplace devolves into "a contest for survival in which the largest and strongest typically win."

Although the Populist Party lasted little more than a decade, the populist movement more generally had a profound impact on the mainstream Democratic and Republican parties. In 1896 and 1900, for example, William Jennings Bryan, referred to in his day as the Great Commoner, was the Democratic nominee for president; and his platform included many populist demands (Bryan lost to William McKinley both times). Populism also overlapped with and influenced many policies associated with the Progressive Movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which was a bipartisan movement that had proponents among both Republicans such as Theodore Roosevelt and Democrats such as Woodrow Wilson (more on this later).

Although the Populist Party lasted little more than a decade, the populist movement more generally had a profound impact on the mainstream Democratic and Republican parties. In 1896 and 1900, for example, William Jennings Bryan, referred to in his day as the Great Commoner, was the Democratic nominee for president; and his platform included many populist demands (Bryan lost to William McKinley both times). Populism also overlapped with and influenced many policies associated with the Progressive Movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which was a bipartisan movement that had proponents among both Republicans such as Theodore Roosevelt and Democrats such as Woodrow Wilson (more on this later).

At its core, historian Michael Kazin thinks that populism is an expression of "profound outrage" against elites, be they economic or political elites, who ignore, corrupt, and/or betray "the core ideal of American democracy." Although this outrage may have no particularly ideological direction--that is, it may be true of people across the political spectrum--populism's appeal to "the people" has often imbued it with common prejudices regarding racial and ethnic minorities, immigrants, and other minority groups. As sociologist Daniel Bell observed, "Social groups that are dispossessed invariably seek targets on whom they can vent their resentment, targets whose power can serve to explain their dispossession." This form of populism, which is characteristic of the political right, does not share the social change objectives of its left-wing counterpart.

Reflecting on the contemporary political scene, some analysts view the Tea Party as a right-wing populist movement that has been co-opted by conservative moneyed interests that favor tax cuts for the wealthy, deregulation of business, and privatization of public programs. The Tea Party emerged in the context of the economic collapse of 2008 and anger over the subsequent government bailout of the "big banks." But it was also fueled by the racial animus that followed the election of Barack Obama and the feeling among conservative white folks that they needed to "take back America." More recently Donald Trump, who has been appealing to popular prejudices about Mexican immigrants and Muslims, has become the most vocal figure on behalf of right-wing populism.

On the left side of the political spectrum, the Occupy protest movement, which peaked between September 2011 and February 2012, heightened public awareness about the growing economic inequality that plagues our country and popularized the distinction between the "99 percent" and the "1 percent." Around that time Elizabeth Warren, who was elected to the U.S. Senate in 2012, also emerged as a key figure in this movement by speaking out against the "big banks" and other "powerful interests" that have captured our government and rigged the system in their favor. Similarly, Bernie Sanders has positioned his presidential campaign in opposition to the "billionaire class" and is calling for the break-up of the large banks that are "too big to fail," mitigating the corrosive influence of Wall Street financial speculation, and getting the "big money" that is corrupting our democracy out of politics.

People in the Wisconsin grassroots community will also recognize the populist strain of Mike McCabe's so-called "blue jeans nation" movement. McCabe likes to call himself a "commoner," which he contrasts with the "royals," eschewing conventional political labels and calling out both Republicans and Democrats for their failure to represent the common people. Rather than framing politics as a matter of left or right, McCabe thinks we should think vertically: "The definitive question in today's politics is not whether you are standing with those on the left, right or middle; it is whether you are with those on the top or bottom or somewhere in between."

What is Progressivism?

As noted, populism overlapped with and influenced the Progressive Movement. According to John Podesta, founder of the Center for American Progress, social and economic justice and a nation of opportunity for all "will be achieved only with an open and effective government that champions the common good over narrow self-interest." He contrasts this with liberalism, which advocates social reforms that provide a "safety net" for people in need but has focused primarily "on preserving human liberty and autonomy and protecting individual rights against encroachment by the state or society."

Whereas populism had a historical base among the rural populace, progressivism had an urban bent. In addition to reforming the working conditions of those who labored in the manufacturing sector of the economy, progressivism aimed to improve the lives of urban dwellers, focusing on public sanitation, public education, healthcare, criminal justice, political corruption, and the development of voluntary community organizations. On the national level, it advocated for more effective antitrust enforcement, food and drug regulation, women's suffrage, an end to child labor, environmental conservation, and progressive income taxation.

Importantly, Dionne notes, "For progressives, there was no sharp separation between the local and national, between charitable work and political work. Progressives such as Jane Addams were nudged toward political action when they concluded that one-on-one social work was insufficient to alleviate the dire conditions that existed in the neighborhoods in which they worked." This observation is reminiscent of what Barack Obama first learned as a community organizer in Chicago before he embarked on his political career.

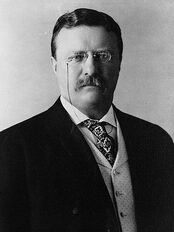

Ironically, in this day and age, it was a younger generation of Republicans, most notably Theodore Roosevelt, who first advanced progressivism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Invoking Lincoln, Roosevelt said that the former president was "for both the man and the dollar, but in case of conflict, the man before the dollar." As governor of New York, Roosevelt worked to separate the government from the businesses that had formerly controlled it by strengthening civil service laws and cracking down on filthy, exploitative sweatshops; and he forced businesses such as street car enterprises that operated in the service of the public to pay taxes they had previously avoided.

Ironically, in this day and age, it was a younger generation of Republicans, most notably Theodore Roosevelt, who first advanced progressivism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Invoking Lincoln, Roosevelt said that the former president was "for both the man and the dollar, but in case of conflict, the man before the dollar." As governor of New York, Roosevelt worked to separate the government from the businesses that had formerly controlled it by strengthening civil service laws and cracking down on filthy, exploitative sweatshops; and he forced businesses such as street car enterprises that operated in the service of the public to pay taxes they had previously avoided.

Roosevelt was President William McKinley's vice-presidential running mate on the ticket that won the election in 1900. When McKinley was assassinated by an anarchist six months after his second inauguration, Roosevelt became president. In his first speech before Congress, in the words of historian Heather Cox Richardson, Roosevelt said that the "government should start cleaning up factories and limiting the working hours of women and children, and it should husband natural resources for everyone rather than allowing them to be exploited by greedy businessmen."

To be sure, Roosevelt was no radical or socialist. He believed that economic concentration in a capitalist system was inevitable and his ultimate goal was not to break up large corporations but rather to supervise and regulate them. Importantly, he sought transparency, that is, he believed that if the public really knew how corporations operated, they would demand more accountability from business leaders.

Roosevelt was re-elected in 1904, the only time he won a presidential election when he was at the top of the ticket. During his subsequent term of office, he read Upton Sinclair's The Jungle, an exposé of the horribly unsanitary conditions in the meatpacking industry, and he pressured Congress to pass the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act of 1906. Insofar as Sinclair's book had triggered a dramatic drop in meat sales due to the loss of public confidence, the larger corporations in that industry actually supported the legislation because government inspection of meat served to restore this eroded confidence. Smaller companies, however, were unable to absorb the additional cost of regulatory compliance and were put out of business.

Ironically, therefore, some attempts to regulate capitalism actually help large corporations consolidate their control of the economy. As Dionne writes, "It would not be the last time capitalism was saved not by its most unapologetic enthusiasts but by critics who understood the system's imperfections and inadequacies and saved it from itself."

Roosevelt did not run for reelection in 1908, and a more conservative Republican, Howard Taft, won the presidency. "A national government," Taft declared, "cannot create good times . . . but it can, by pursuing meddlesome policy, attempting to change economic conditions, and frightening the investment of capital, prevent prosperity and a revival of business which might otherwise have taken place." According to historian John Milton Cooper, Taft "marked an early step toward the ideological transformation of the Republican Party" in a more conservative direction from that point forward.

Progressive Republicans were disappointed with Taft's conservatism, and as the 1912 presidential election approached, they turned to Roosevelt to revive their political aspirations. But Roosevelt was unable to dislodge Taft, who received his party's nomination, and he and his followers decided to mount a third-party campaign, forming the Progressive Party, also known as the Bull Moose Party, because of Roosevelt's reputation as a big-game hunter.

It is important to note that progressivism was a bipartisan movement, and on the Democratic side Woodrow Wilson, who served as governor of New Jersey, was the most prominent of the early progressives to reach the presidency, winning the election in both 1912 and 1916 while campaigning for a stronger federal government, antitrust enforcement, and labor rights.

In some ways, at least rhetorically, Wilson was a more strident opponent of corporate concentration than Roosevelt. As he asked, in an effort to distinguish himself from Roosevelt, "Have we come to a time when the President of the United States or any man who wishes to be President must doff his cap in the presence of high finance and say, 'You are our inevitable master, but we will see how we can make the best of it?'" And he warned that the United States was nearing "the time when the combined power of high finance would be greater than the power of the government." In the current Democratic presidential campaign, it is fair to say that Hillary Clinton has fashioned her claim to progressivism in the manner of Theodore Roosevelt, whereas Bernie Sanders has fashioned himself in the tradition of Wilson.

Before concluding this article, it is worth mentioning the contribution of Wisconsin's Robert La Follette, the heir to Theodore Roosevelt's 1912 Progressive Party and the man whom Franklin Roosevelt acknowledged as an inspiration for his own reform-minded agenda.

La Follette, as a member of the Republican Party, was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1885 and to the governorship in 1900. From 1906 to 1925 he represented Wisconsin in the U.S. Senate. During this period he was the most important figure in Wisconsin politics and helped make the state one of the most progressive in the nation. Those of us who are familiar with this history are all the more saddened by the current political climate in our state.

La Follette, as a member of the Republican Party, was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1885 and to the governorship in 1900. From 1906 to 1925 he represented Wisconsin in the U.S. Senate. During this period he was the most important figure in Wisconsin politics and helped make the state one of the most progressive in the nation. Those of us who are familiar with this history are all the more saddened by the current political climate in our state.

In 1912 La Follette had been a serious contender for the Republican Party nomination for president, and in 1924 he broke with his party--which nominated the conservative Calvin Coolidge, who won the election--and ran as the Progressive Party candidate, with the endorsement of the Socialist Party, receiving 17 percent of the national vote. His campaign platform, in the words of journalist John Nichols, "called for government takeover of the railroads, elimination of private utilities, easier credit for farmers, the outlawing of child labor, the right of workers to organize unions, [and] increased protection of civil liberties," and he pledged to "break the combined power of the private monopoly system over the political and economic life of the American people."

Conclusion

The populist and progressive traditions in American politics prefigured many of the reforms that were enacted through Franklin Roosevelt's "New Deal" policies of the 1930s. It was during that era, for example, that the National Labor Relations Act was passed, which for the first time guaranteed the right of workers to organize labor unions.

In addition, the Glass-Steagall Act was passed, which created a wall of separation between traditional commercial banks, which receive deposits that are insured by the federal government and lend money to borrowers, and investment banks, which raise uninsured capital for risky high-stakes investments, trade in stocks and other financial securities, and manage corporate acquisitions and mergers. (In an alliance between President Bill Clinton and a Republican-controlled Congress, Glass-Steagall was repealed in 1999. Currently Bernie Sanders favors reinstatement of Glass-Steagall while Hillary Clinton does not.)

During the 1930s, too, federal regulatory law was expanded with the establishment of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Federal Housing Administration, among other agencies. And the first incarnation of social security was passed, providing financial support for the elderly, the unemployed, widows, the blind, and destitute children and children with disabilities.

According to Dionne, the New Deal "accepted and fostered a cooperative connection between government and the private economy. It understood government's role as constructive, and assigned government a moral responsibility." As Franklin Roosevelt himself said, "Better the occasional faults of a government that lives in a spirit of charity than the consistent omissions of a government frozen in the ice of its own indifference."

The New Deal and the policy heirs to this legacy, which included Democratic president Lyndon Johnson's "Great Society" programs of the 1960s, saved capitalism for several decades. By providing needed reforms and helping to build the American middle class, it arguably prevented the desperation that gave rise to the authoritarian and fascist movements that emerged in Europe in the 1930s. At the same time, it also stunted the development of a viable socialist movement in the United States, or what Europeans generally call social democracy and Bernie Sanders calls democratic socialism.

Up until the 1970s, corporate leaders tended to view themselves as having a moral responsibility to balance the claims of stockholders, employees, and the general public. For reasons that are beyond the scope of this article, this is no longer the case. These leaders and the political class that does its bidding no longer believe they have a responsibility to provide for shared prosperity, or in the words of our Constitution's Preamble, to "promote the general welfare." And a large portion of the citizenry, whether by intention, inattention, apathy, or despair, is no longer trying to make them do so. It is our task and responsibility to future generations to try to change this state of affairs.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jeff Berger, Charles Cottle, Richard Haney, and Randy Stoecker for their feedback on this article.

Sources

Brian Balogh. 2009. A Government Out of Sight: The Mystery of National Authority in Nineteenth-Century America. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Daniel Bell (ed.). 1963. The Radical Right. New York: Doubleday.

John Milton Cooper. 2009. Woodrow Wilson: A Biography. New York: Knopf.

E. J. Dionne Jr. 2012. Our Divided Political Heart: The Battle for the American Idea in an Age of Discontent. New York: Bloomsbury.

Michael Kazin. 1995. The Populist Persuasion: An American History. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Mike McCabe. 2014. Blue Jeans in High Places: The Coming Makeover of American Politics. Mineral Point, WI: Little Creek Press.

John Nichols. 1999. "Portrait of the Founder, Fighting Bob La Follette." The Progressive, vol. 63, issue 1.

Barack Obama. 2004. Dreams From My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance. New York: Broadway.

John Podesta. 2008. The Power of Progress: How America's Progressives Can (Once Again) Save Our Economy, Our Climate, and Our Country. New York: Crown.

Robert Reich. 2015. Saving Capitalism: For the Many, Not the Few. New York: Knopf.

Heather Cox Richardson. 2014. To Make Men Free: A History of the Republican Party. New York: Basic Books.

Michael Sandel. 1996. Democracy's Discontent: America In Search of a Public Philosophy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Theda Skocpol & Vanessa Williams. 2012. The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism. New York: Oxford University Press.