Ron Berger --

This article was initially published on Wise Guys, Jan. 8, 2020.

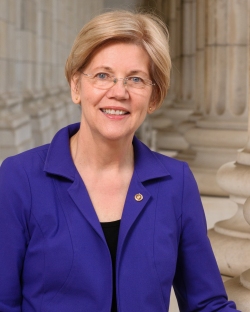

When I think about the myriad issues that are being raised during the current Democratic Party presidential primary, I am reminded of the advice given by James Carville, Bill Clinton’s political strategist, during the 1992 presidential campaign: “The economy, stupid.” It is often the case, however, that when people think about the economy they are thinking about elements such as un/employment, economic inequality, wages, the stock market, economic growth, and the like. What they tend not to be thinking about is antitrust law. To some, antitrust law seems like an esoteric topic. But it should not be. In fact, it should be at the forefront of policies that are being discussed by the presidential candidates and that need to be pursued by the next Democratic president. Among the candidates, to their credit, Senators Amy Klobuchar (MN), Bernie Sanders (VT), and Elizabeth Warren (MA) are the only ones who have spoken about and offered plans to make antitrust law enforcement a priority for their administrations, with Warren offering the most far-reaching and detailed plans overall.

The initial framework for antitrust law in the United States was the Sherman Antitrust Act (SAA) of 1890. For the first time in history, the SAA redefined previously legal business combinations that resulted in a restraint of trade (including cooperative agreements to fix prices above competitive market rates) or the monopolization or attempted monopolization of an industry as subject to criminal and civil legal penalties. “Antitrust” got its name because the law was a response to the practice by which corporations had entered into cooperative units called “trusts” or “holding companies,” whereby a board of trustees coordinated the activities of its member companies, who agreed to surrender their autonomy to a centralized authority.

Unfortunately, over the years, antitrust law has been practiced more in its breach, and it has not stopped the march of corporate consolidation in any significant way. Consequently, in industry after industry in the United States, a half dozen or fewer corporations—in some cases as few as two or three—now control their respective markets by means of a business model that is built on the collapse of meaningful antitrust law enforcement. This unregulated corporate concentration has had deleterious effects not only on the economy, but on the political system. As Sandeep Vaheesan, legal director of the Open Markets Institute and former regulations counsel at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, observes, “Corporate concentration has meant that ordinary Americans pay more for essentials, earn less at work, lose opportunities to start new businesses, and are forced to accept corporate control of politics,” as corporations spend massive amounts of money to lobby and elect politicians who will do their bidding. It is therefore incumbent upon us to take seriously the dictum of Justice Louis Brandeis, who served on the US Supreme Court from 1916 to 1939: “We must make a choice. We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.”

In this article, I place this state of affairs in historical context, review some of the adverse consequences of lax antitrust law enforcement, and identify a number of actions that a new Democratic president could take to reinvigorate antitrust law to address the problem of too much corporate concentration. In doing so, I premise my argument on the assumption that the existence of a so-called “free market” independent of government is a myth, because it is government that sets the rules of the marketplace. In other words, as economist Robert Reich observes, government does not “intrude” on the market but rather “creates the market.” This view stands in marked contrast to the one espoused by contemporary conservatives and libertarians who believe that the market exists as a natural force by which economic actors compete to advance their self-interest and in doing so produce beneficial outcomes not only for individual competitors but for society at large.

Historical Background

The emergence of modern capitalism and the industrial revolution, which began in Great Britain and took hold in the United States in the 19th century, went hand in hand. Capitalism is a system of private ownership of the dominant means of economic production in a given society, while industrialization is the process of utilizing power-driven machinery and factory organization in the production process. In the United States, following the Civil War, these twin systems of production dovetailed with westward expansion and fueled unprecedented economic growth.

At this time as well, the “corporation” emerged as the capitalist economic unit most capable of coordinating and rationalizing large-scale economic activity and providing a vehicle for the concentration of investment capital. Through the legal chartering of corporations, the government (mostly state governments) granted these enterprises the right to own property, manufacture and buy and sell products, and bring lawsuits as if they were individual persons.

In the latter part of the 19th century, the railroads played a key role in the expansion of corporations by providing a system of transportation that integrated the nation into a single marketplace. Thus, retail companies like Montgomery Ward and Sears Roebuck were able to sell their products directly to consumers through mail-order catalogs. Similarly, national “chain” stores were able to integrate wholesaling, distributing, and retailing functions; guarantee sufficient supply and uniform products; and extend credit to subsidiaries.

The corporate mode of organization proved highly suitable to the national marketplace. Its military-like, top-down organizational structure was capable of administering hundreds of subunits across a wide geographic territory. An expanded cadre of professional executives, middle-level managers, and functional and technical specialists worked together, in the words of sociologist James Inverarity and colleagues, “to mobilize capital, equipment, technological talent, and labor over the extended periods associated with modern industrial production.” One of the problems facing corporations, however, was their inability to rationalize or achieve predictability in the marketplace. Competition among firms threatened their profitability, even their survival. Businessmen came to realize that cooperation might serve them better than competition. Railroads, for example, entered into pools or trade associations that fixed rates of profit and allocated business among competing lines. And, as noted earlier, some corporations entered into trusts or holding companies to avoid competition.

It is noteworthy that this era was called the “Gilded Age,” a term coined by Mark Twain, which referred to the predatory business practices, financial misdealings, audacious display of wealth, and high level of economic inequality that marked the late 19th century, when 2 percent of US households owned more than a third of the nation’s wealth. To many Americans at the time, the aforementioned business combinations that were at the heart of the Gilded Age were antithetical to a “free market” competitive economy. Farmers and small business owners decried these anticompetitive organizations, holding them responsible for rising costs, falling prices, increased debt, and massive foreclosures. They formed local “antitrust leagues” that lobbied for reform, and in 1890 the US Congress passed the landmark Sherman Antitrust Act, named after its author, John Sherman, a Republican Senator from Ohio who previously served as Secretary of Treasury and Secretary of State. When Sherman introduced his legislation, he described it as a means of addressing the “inequality of condition, of wealth, and opportunity that had grown within a single generation out of the concentration of capital into vast combinations to control production and trade.”

It is noteworthy that this era was called the “Gilded Age,” a term coined by Mark Twain, which referred to the predatory business practices, financial misdealings, audacious display of wealth, and high level of economic inequality that marked the late 19th century, when 2 percent of US households owned more than a third of the nation’s wealth. To many Americans at the time, the aforementioned business combinations that were at the heart of the Gilded Age were antithetical to a “free market” competitive economy. Farmers and small business owners decried these anticompetitive organizations, holding them responsible for rising costs, falling prices, increased debt, and massive foreclosures. They formed local “antitrust leagues” that lobbied for reform, and in 1890 the US Congress passed the landmark Sherman Antitrust Act, named after its author, John Sherman, a Republican Senator from Ohio who previously served as Secretary of Treasury and Secretary of State. When Sherman introduced his legislation, he described it as a means of addressing the “inequality of condition, of wealth, and opportunity that had grown within a single generation out of the concentration of capital into vast combinations to control production and trade.”

By the turn of the 20th century, trusts per se were becoming obsolete business enterprises, but monopolies were not, and people at the time used the two terms interchangeably. Narrowly speaking, a monopoly connotes one firm that dominates a particular industry, in contrast to an oligopoly, which connotes an industry that is dominated by a few firms. Nevertheless, the key issue with respect to antitrust law is the degree of corporate concentration and the ways in which such concentration can lead to noncompetitive business practices.

Overall, between 1895 and 1904, 157 corporations absorbed more than 1,800 companies, and the large majority of these firms controlled more than 40 percent of the market—which, in addition to the railroads, included the oil, steel, sugar, tobacco, whiskey, meat-packing, and cash-register industries as among the most concentrated. Thus, the SAA did not have an immediate impact on the suppression of corporate concentration. One reason for this is that Congress did not allocate additional funds for antitrust enforcement, and a separate antitrust division in the Department of Justice (DOJ) was not created for another 13 years. Up until then, the DOJ initiated just six criminal cases and 16 civil cases. Among these, only one criminal case and three civil cases were successfully prosecuted, and no one was incarcerated.

Although the US Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the SAA, laying the groundwork for further expansion of federal regulatory law, the Court narrowed the scope of the SAA’s authority, ruling in 1895 that the law did not apply to companies that manufactured their products within a single state. Thus the American Sugar Refining Company, for instance, which accounted for 98 percent of the country’s sugar manufacturing, was not considered an illegal monopoly.

Theodore Roosevelt

In the first decade of the 20th century, Republican President Theodore Roosevelt emerged as the leading advocate of antitrust law enforcement. All told, some 40 trusts that had been formed in the 1890s were dismantled. Still, Roosevelt made a distinction (borrowed from financier Charles Schwab) between “good trusts” and “bad trusts.” Whereas bad trusts engaged in unfair noncompetitive practices, good trusts inevitably emerged from the technical conditions necessary for rational and efficient economic production and business administration. In 1911, the US Supreme Court enshrined this view into antitrust law in cases involving the Standard Oil Company and American Tobacco Company, when it ruled that these companies had violated the SAA. The Court ordered Standard Oil broken up into 34 companies, many of which subsequently recombined, and American Tobacco broken up into four firms. In doing so, however, the Court asserted that the SAA applied only to “unreasonable” and not “reasonable” business combinations.

Subsequently, during the Democratic administration of President Woodrow Wilson, Congress strengthened the SAA by passing the Clayton Act in 1914, which specified prohibited conduct to include, among other things, mergers and acquisitions that substantially lessened competition. That same year, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Act was passed, which established a federal agency to oversee and enforce antitrust law. However, this was not an indictment of large corporations per se. As Wilson said, “I am for big business, and I am against the trust.”

The upshot of these reforms was the diffusion of anti-monopoly agitation that had led to the SAA in the first place. Egregious cases like Standard Oil and American Tobacco would be dealt with, but the consolidation of corporate America would continue unabated. Some federal regulation of the economy would help stabilize the economy and achieve more market predictability, but the moral stigma associated with antitrust violations would dissipate. Moreover, it was not until the 1950s that any of the small number of corporate executives who were found to be in violation of the SAA received any jail time, and this was for an egregious price-fixing case in which executives in the electrical equipment industry, who netted millions of dollars in illegal profits for their companies, received 25-day jail sentences. At trial, one executive remarked that price-fixing “had become so common and gone on for so many years that I think we lost sight of the fact that it was illegal.”1

The Failure of Antitrust Law

Currently, antitrust law refers to a collection of federal and state laws and judicial decisions regarding the regulation of anticompetitive practices in the United States. Over the years, while some concentrated industries have been broken up and mergers prevented, corporate America overall has become more consolidated. Part of what happened over the last half century is that antitrust law was increasingly interpreted in terms of its effect on “consumer welfare” rather than on market competition and, in the words of law professors Maurice Stucke and Ariel Ezrachi, in terms of “the historic concern about halting the momentum toward … concentrated economic power.” This consumer viewpoint was promoted by the Chicago School of Economics and one of its key disciples, Yale law professor Robert Bork, later a federal judge and failed nominee to the US Supreme Court. It was this approach that achieved hegemonic status during the Republican administration of Ronald Reagan in the 1980s through, in Stuckey and Ezrachi’s words, “its enforcement priorities, judicial appointments, and amicus briefs to the Supreme Court.” Even during the subsequent Democratic administrations of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, the “government rarely challenged mergers among economic competitors”—whether they were horizontal mergers, that is, mergers between competitors making and selling similar products in a particular market or industry, or vertical mergers, that is, mergers between companies at different stages of the production process or supply chain.2 As economist Robert Kuttner bluntly puts it, “Antitrust enforcement collapsed under both parties.”

As a result, during the last two decades alone, more than three-quarters of US industries have undergone increased levels of corporate concentration, and in the name of economic efficiency, employees have been cut and/or their wages suppressed, in spite of (or because of) their increased productivity. In the short run, consumers may pay lower prices, but in the long run the lack of competition increases prices, and the loss of jobs associated with these mergers has suppressed wage growth and consumer buying power. In large part, consumption over the last few decades could not have been sustained without massive consumer debt, and nowadays 40 percent of Americans don’t have enough cash on hand to cover an unexpected expense of $400.

One of the ways in which large corporations exert oligopolist control of the respective markets is by buying out companies that challenge their dominance, often at the expense of stifling innovation. For example, Kuttner points out that over the last decade “Amazon, Apple, Google, Facebook, and Microsoft have brought 436 rival companies, without any regulatory challenge.” A few consequences of this is that Google and Facebook now sell 80 percent of all internet ads, sites owned by Facebook garner 85 percent of all social networking traffic, and Amazon controls nearly half of all e-commerce. It is also problematic that Amazon takes unfair advantage of its digital sales platform by monitoring consumers’ interest in the products of other companies that are sold on its platform and then marketing its own branded products to undercut these competitors. Elizabeth Warren likens Amazon to a baseball umpire that also fields its own team. This, Warren believes, should not be allowed; you shouldn’t “get to do both at the same time.”

One of the ways in which large corporations exert oligopolist control of the respective markets is by buying out companies that challenge their dominance, often at the expense of stifling innovation. For example, Kuttner points out that over the last decade “Amazon, Apple, Google, Facebook, and Microsoft have brought 436 rival companies, without any regulatory challenge.” A few consequences of this is that Google and Facebook now sell 80 percent of all internet ads, sites owned by Facebook garner 85 percent of all social networking traffic, and Amazon controls nearly half of all e-commerce. It is also problematic that Amazon takes unfair advantage of its digital sales platform by monitoring consumers’ interest in the products of other companies that are sold on its platform and then marketing its own branded products to undercut these competitors. Elizabeth Warren likens Amazon to a baseball umpire that also fields its own team. This, Warren believes, should not be allowed; you shouldn’t “get to do both at the same time.”

The editors of The Nation magazine point out that Amazon does not just desire “to dictate the market; it seeks to replace the market entirely,” and other ways it does this is by temporarily selling items below cost to push rival retailers out of business. They also squeeze their suppliers, who are forced to lower their prices and pay large transaction fees, hence undermining their sustainability. It is noteworthy that Walmart, which accounts for about 9 percent of retail sales in the United States, engages in similar business practices.

The agricultural industry is another overly concentrated market where Monsanto, which recently merged with Bayer, now controls nearly 40 percent of the vegetable seed market overall, 80 percent of the corn, and more than 90 percent of the soybeans planted in the United States. Robert Reich adds that Monsanto has “patented its own genetically modified seeds, along with an herbicide that … kill[s] weeds but not soy and corn grown from its seeds,” and to ensure its market dominance, it prohibits “seed dealers from stocking its competitors seeds and has bought up most of the remaining seed companies.” This monopolistic practice, which has been permitted by the government, keeps farmers dependent on one company and forces them to pay higher prices, while also dramatically reducing “the genetic diversity of the seeds we depend on.” In addition, Monsanto has successfully lobbied against laws that would “require labeling of genetically engineered foods … [and] protect biodiversity.”

Other areas of the economy that are dominated by oligopolies include:

- four beef companies—Tyson Foods, JBS, Cargill, National Beef—that produce more than 85 percent of beef sold in the United States

- three chicken companies—Tyson Foods, Pilgram’s, Sanderson Farms—that produce nearly half of chickens

- two beer companies—Anheuser-Busch, MillerCoors—that sell more than 70 percent of beer

- three drugstores chains—CVS, Walgreens, Rite Aid—that control 99 percent of the retail pharmacy industry

- five health insurance companies—United Health Group, Anthem, Aetna, Cigna, Humana—that dominate more than 80 percent of the private insurance market

- three smartphone companies—Apple, Samsung, LG—that sell nearly 80 percent of smartphones

- four airline companies—American, Delta, United, Southwest—that sell more than 80 of domestic airline seats

- four cable providers—ATT, Charter, Comcast, Dish Network—that service 85 percent of cable subscribers

- six media (TV, film, print, internet, video) companies—GE, News-Corp, Disney, Viacom, Time Warner, CBS—that control 90 percent of the media

According to Warren, these statistics are a reminder that giant corporations and concentrated industries “touch every aspect of our lives—but also a reminder that it doesn’t have to be this way.” ‘

What Can Be Done

Not since the Gilded Age have levels of economic inequality in the United States been so high, with just 1 percent of the population owning some 40 percent of the nation’s wealth. The reinvigoration of antitrust law is one way to reverse this unsustainable situation, which is threat to both our economic and political well-being. Even without the passage of new legislation, Sandeep Vaheesan identifies a number of things a new Democratic president could do by appointing reform-oriented officials to the FTC, DOJ Antitrust Division, and US Department of Agriculture (USDA).

For starters, under the Federal Trade Commission Act the FTC is authorized to identify and prohibit “unfair methods of competition,” and in the FTC v. Sperry & Hutchinson decision of 1972, the US Supreme Court stated that the FTC can establish rules of the marketplace that consider “public values beyond simply those enshrined in the letter or encompassed in the spirit of the antitrust laws.” This established a broad mandate, in Vaheesan’s words, “to create a fair marketplace and prohibit abusive, exclusionary, and predatory business practices.”

Vaheesan suggests that one of the reforms that a revived FTC could undertake is the overturning of a rule that has allowed employers to impose noncompetetive contractual agreements on millions of workers throughout the economy. These contracts allow employers to “prevent workers from taking a new position or starting a business in their field or industry after leaving their current employer” for a specified period of time, a practice that impairs worker mobility, depresses wages, impedes the formation of new firms, and prevents “workers from leaving abusive or unsafe environments.”

Another reform that the FTC could pursue is enactment of a rule that prohibits monopolistic practices that “block new rivals, handicap competitors, and deprive customers of choice.” For example, dominant firms in the tech industry have forced exclusive contracts on wholesalers, suppliers, and customers that prevent them from doing business with competitors, or they have offered them financial inducements for not doing so. In either case, Vaheesan believes that these practices foreclose fair competition.

Vaheesan also thinks that the FTC can play a role in lowering prescription drug prices by going after pharmaceutical corporations that pay rivals to not introduce lower-priced generic drugs. It could also prevent drug companies from extending their patents “on trivial reformulations of existing drugs” and from encouraging “doctors to prescribe the new drug in place of the current version.”

Elizabeth Warren

Turning to the question of corporate consolidation and mergers, Vaheesan would have the FTC and DOJ dust off the part of the Clayton Act that permits restriction of “mergers and acquisitions between direct rivals.” Unfortunately, since the administration of Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, the FTC and DOJ “have steadily raised the market threshold” for challenging mergers; hence we now live in an era of mega-mergers of already huge corporations. Back in the 1960s, in contrast, a merger that created a firm with a market share of more than 10 percent would have been disallowed. Currently, Elizabeth Warren has proposed a bill that would prohibit mergers of firms with a market share of 25 percent or more. Warren also wants to reverse already existing anticompetitive mergers, such as the recent merger of Monsanto and Bayer, as well as Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram and WhatsApp. She would also have Amazon spin off or shutter its own private brands, such as Amazon Basics, and relinquish its ownership of Whole Foods and Zappos. Additionally, Warren is proposing legislation that would transform large tech platforms into public utilities, that is, businesses that provide everyday essentials such as water, electricity, natural gas, and telephone service. Public utilities tend to be considered reasonable “natural monopolies,” because the infrastructure required for them are very expensive to build and maintain. They can be publicly or privately owned and operated, but most are private. Because utilities offer essential services, they can be regulated for the overall good of society. According to Warren’s plan:

Companies with an annual global revenue of $25 billion or more and that offer to the public an online market, an exchange, or a platform connecting third parties would be designated as “platform utilities.” These companies would be prohibited from owning both the platform utility and any participants on the platform. Platform utilities would be required to meet a standard of fair, reasonable, and nondiscriminatory dealing with users … [and] would not be allowed to transfer or share data with third parties. For smaller companies (those with annual global revenue of between $90 million and $25 billion), their platform utilities would be required to meet the same standard of fair, reasonable, and nondiscriminatory dealing with third parties, but would not be required to structurally separate from any participant on the platform.

Still another area of reform involves the restoration of consumers’ rights to repair the products they purchase at an independent repair shop or to repair them on their own. Currently, corporations like Apple, John Deere, and Honda are able, in Vaheesen’s words, to limit “the availability of spare parts and schematics, bundling new parts with repair service, and redesigning products to limit easy services.” Thus, “owners of a wide range of durable goods are compelled to get costly repairs done by manufacturers or manufacturer-authorized technicians.” However, in the 1992 case of Eastman Kodak Co. v. Image Technical Services, the Supreme Court ruled that competition in the primary market for a product does not preclude enforcement of antitrust law for “abuse in the aftermarket for parts and services.”

Lastly, Vaheesan points to the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1922 as authorizing the USDA to protect chicken, hog, and livestock producers from abuse by powerful buyers and processors. More recently, following the passage of the 2008 Farm Bill, the USDA during the administration of Barack Obama sought to establish rules that would limit processors’ ability to engage in price discrimination, particularly for retaliation against producers who air grievances or engage “in cooperation with other producers,” and it would prevent processors from giving bonuses to favored producers at the expense of others. The Obama USDA also sought to permit producers to decline private arbitration of legal disputes, giving them the right to resolve their grievances in a court of law. However, industry trade groups lobbied against these provisions, and when the Republicans took control of the House of Representatives in 2010, they barred the USDA from finalizing these rules for several years. Once Donald Trump came into office, he “moved to repeal these protections” altogether.

Certainly much more could be done to address the problem of corporate concentration by means of legislation rather than agency action alone. For example, both Warren and Sanders have called for the reinstatement of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, the depression era reform that created a wall of separation between traditional commercial banks, which receive deposits that are insured by the federal government and lend money to borrowers, and investment banks, which raise uninsured capital for risky high-stakes investments, trade in stocks and other financial securities, and manage corporate acquisitions and mergers. In an alliance between President Bill Clinton and a Republican-controlled Congress, Glass-Steagall was repealed in 1999, leaving taxpayers vulnerable to bailing out banks that lost federally-insured monies due to the unregulated financial speculation that culminated in the financial crisis of 2008. Warren and Sanders have also called for breaking up banks that are “too big to fail.” As Sanders has said, if banks are too big to fail, they are “too big to exist.”

Regarding the economy more generally, Vaheesan concludes that even without new legislation, the next Democratic president will have the ability to “limit corporate power with the awesome anti-monopoly authorities already invested in the DOJ, FTC, USDA, and other federal agencies. … A president determined to achieve those goals will have the tools to do it on January 20, 2021.”

Notes

1. It is noteworthy that labor and union defendants, not corporate executives, were the first 11 individuals to be imprisoned for antitrust violation. Law professor Sanjukta Paul notes that prior to the 1930s, when “workers’ right to organize unions and bargain collectively” was recognized under federal law, antitrust law was used “to punish and inhibit labor strikes and other expressions of solidarity.” Nowadays, it is being used to prevent workers who attempt to organize outside of unions from “exercising collective power.” For example, if a group of independent truck drivers, small group of suppliers, or Uber drivers get together to bargain over prices and wages, that association is considered illegal. Paul describes this as a case of antitrust law being turned “upside down,” because the SAA was never intended “to prohibit economic cooperation among workers, small farmers, and other small producers.”

2. To its credit, the Clinton administration undertook a significant antitrust case against Microsoft, and in 1999 a federal judge ruled that the company had abused the virtual (but reasonable) monopoly it had on its Windows operating system to gain an unfair advantage over competitors on the sale of other products. The most egregious practice involved Microsoft exerting pressure on retailers who sold Windows to also sell Microsoft’s Internet Explorer rather than the Netscape Navigator browser. At one time, Netscape had controlled a larger share of the Internet browser market, but Microsoft soon dominated this area. Microsoft also denied competitors technical information about Windows, which caused problems for consumers who used other companies’ product. The judge in the case recommended breaking up Microsoft into two or more companies, but when the George W. Bush administration came into office a settlement was reached that kept the company in tact but required Microsoft to provide competitors with technical information that would allow them to run more seamlessly with Windows. Warren credits this lawsuit with clearing the path for the success of Google and Facebook.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Charles Cottle and Jeff Berger for their input on this article.

Selected Sources

James Inverarity, Pat Lauderdale & Barry Feld (1983). Law and Society: Sociological Perspectives on Criminal Law. Little, Brown.

Robert Kuttner (2019). The Stakes: 2020 and the Survival of American Democracy. Norton.

Albert McCormick (1977). “Rule Enforcement and Moral Indignation: Some Observations on the Effects of Criminal Antitrust Conviction upon Societal Reaction Processes.” Social Problems 25, pp. 30-39.

The Nation (2018). “The Monopoly Menace” (Mar. 12), p. 3.

W. Lawrence Neuman (1998). “Negotiated Meanings and State Transformation: The Trust Issue in the Progressive Era.” Social Problems 45, pp. 315-335.

Sanjukta Paul (2019). “The Double Standard of Antitrust Law.” The American Prospect (Summer), pp. 40-42.

Robert Reich (2015). Saving Capitalism: For the Many, Not the Few. Knopf.

Maurice Stucke & Ariel Ezrachi (2017). “The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of the U.S. Antitrust Movement.” Harvard Business Review (Dec. 15).

Sandeep Vaheesan (2019). “Unleash the Existing Anti-Monopoly Arsenal.” The American Prospect (Fall), pp. 21-23.

Elizabeth Warren (2017). This Fight Is Our Fight: The Battle to Save America’s Middle Class. Metropolitan Books.

Elizabeth Warren (2019). “It’s Time to Break Up Amazon, Google, and Facebook.” Medium (Mar. 8), http://www.medium.com.

George Zornick (2018). “The Big Fight.” The Nation (Mar. 12), pp. 13-14.